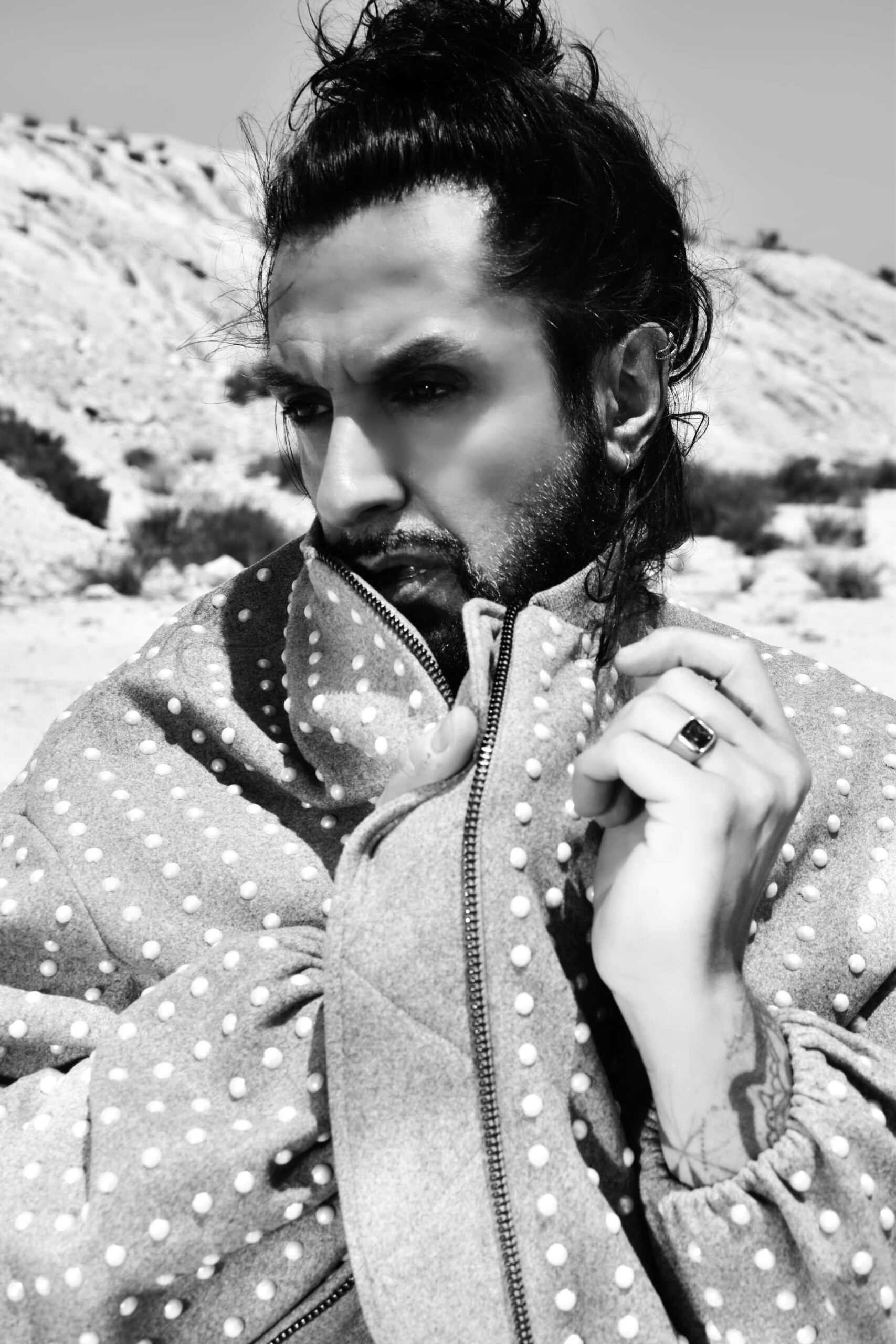

Dancer, Choreographer, Actor and Director

Was born on January 3, 1975, in Valderrubio (Granada), Spain. From his legendary maestros he studied classical flamenco but in his choreography he imaginatively incorporates other types of dance. He expanded his repertoire of dance by attending the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance in New York in 1996.

In 1997, he accompanied singer Gala as a dancer on her shows during the tour for her album “Come into my life.” They continue to perform together occasionally to this day. He has worked on two productions at the Mérida International Classical Theatre Festival: Prometeo, alongside Antonio Canales, in 2000; and Troya Siglo XXI, alongside dancer María Jiménez and actress Án-

gela Molina, in 2002. In 2019, he also presented his own production, Dionisio, at the 65th edition of the Festival.

In 2000 he collaborated on the soundtrack for the film Gladiator, with music by Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrad. The film won a Golden Globe for Best Original Score and was also nominated for an Oscar and a BAFTA Award in the same

category.

In 2007, he choreographed the musical Zorro for London’s West End, with music by Gipsy Kings and John Cameron (Les Misérables), stage direction by Christopher Renshaw (West-End director of musicals such as The King and I and We Will Rock You), co-produced by writer Isabel Allende.5 A show for which he was nominated for the Lawrence Olivier Awards as Best Theatre Choreographer.This are just few performances of Amargo as he has a long list of worldwide performances.

Amargo’s choreography overflows with both traditional and modern concepts that are perfectly matched together. His routines are often heavily influence by modern dance but he never strays far from his flamenco roots. His consistent interaction with the wide world of contemporary dance helped him explore new horizons with his choreographies. Rafael Amargo is not only globally

recognized as the most prominent Spanish flamenco dancer and choreographer but his popularity has given rise to acting and directing opportunities as well.

“I’m worth more for what I keep silent than for what others say about me.”

Can you share a little about your background? Where did you grow up, and what were your early influences in dancing?

I was born in a small village in Granada, the same place where the poet Federico García Lorca was born. I’m LORQUIANO — that’s why my name is Amargo. When I saw the film by Carlos Saura with Antonio Gades, I turned to my father and said, “I want to be like that man.” So he enrolled me in a dance and acting school — and here I am, still going.

Rafael, you’ve been called “the last dancer of a generation that broke with everything.” When you look back, what do you think that generation changed in flamenco and in the arts?

Well, that’s a big responsibility… I think it happened because, in a very short period of time, I created several major ballets and built a repertoire that was praised by both critics and audiences.

What’s a typical day like for you? How do you balance your time between dance, work, and personal life?

Well, the most sensible thing to say is that for me, no two days are ever the same. I only really have a routine when I’m in the middle of creating a new piece — like these days — so my days are mostly focused on rehearsals. That’s the core of everything else, like production work and all the rest.

You’ve often said that you’ve lived without missing out on what youth deserves. What lessons has that intensity of living taught you today?

Well… I shouldn’t have been so generous — not everyone deserves as much as I’ve given. And in life, “there’s no greater truth than the fact that everything is a lie.”

Your life has had both triumphs and trials — what do you think has been your greatest victory and your greatest test?

My greatest achievement is having created art and a repertoire that have been applauded, and having made my name known around the world. There are many great artists, but not all of them have the visibility they’d like — and I’ve had more than plenty of it.

You’re known for being a Renaissance man — dancer, choreographer, writer, and now musician. What drives you to constantly explore new artistic languages?

My curiosity comes from the coincidences and causes of this crazy, wonderful life… What I try to do through that exploration is grow. In the end, artists are artists — and that means many different facets.

“Flamencograma,” your upcoming album with DJ Dany Cohiba, merges electronic music with flamenco. How did the idea of electro-flamenco come about, and what do you want listeners to feel when they hear it?

FLAMENGOGRAMA is a collaboration with a wonderful person as well as an artist, Dany Cohiba. He was familiar with my work, and we met on a radio program — that’s where this partnership began. He is also creating the music for ALA! IRÉ, my new show, which premieres on December 8 in San Lorenzo del Escorial, then on the 13th in Serranillos del Valle, and on the 27th at the Center for Humanities in La Cabrera, Sierra Norte, Madrid.

Your version of Carmen will premiere at the Venice Biennale, one of the world’s most prestigious stages. What does this project represent for you personally and artistically?

Well, I hope so! It’s a proposal, and now Matthew Bourne has to choose me. But with or without the Biennale, I will make this production happen, because it’s a wonderful piece — and, besides, no man has ever stepped into Carmen’s shoes before.

You’ve been portrayed by great visual artists and photographers, from Bruce Weber to Annie Leibovitz and Domingo Zapata. How does it feel to be the subject of other creators’ inspiration, when you’re usually the one creating?

Well, in most cases, I was approached by magazine publishers, so of course they made the choices… Faces of Spain sought me out as an icon or reference of flamenco in the world. In Ruven Afanador’s case, it was for his book Ángel Flamenco. Bruce Weber featured me for L’Uomo Vogue in Italy. And with Domingo Zapata, who is a friend, I’ve danced at Art Basel Miami for him, and we’ve created pieces together.

Your novel El hijo de la Macorina is already in its second edition, and you’re finishing your second book. What inspired you to write, and how does writing compare to dance as a form of expression?

I started writing the book while deprived of my freedom — it was the best way to pass the time. At least I was able to recycle into art the huge injustice, as the courts themselves called it, that was done to me, after being found completely innocent and acquitted. Perhaps I wouldn’t have written the book if it hadn’t been for being without a phone, without socializing, and so on.

In your biography, there’s mention of your generosity and empathy — that you suffer the pain of others as much as your own. How do you channel that sensitivity into your art?

I try not to mix who I am with what I do, or what I want people to see in me as an artist. I am different from who I am as a person or human being without my art.

What are some of your hobbies or interests?

I’m very interested in cinema… And lately, I’ve been spending a lot of time reading. I also enjoy using my graphic design app — composing, calligraphy, all of that really interests me.

You’ve said you’d rather lose a fan than a minute of your life. What does that say about your philosophy today, after everything you’ve lived?

Well, the answer is very clear — right now, I dedicate more time to myself than to anyone else.

Many young dancers and artists see you as a reference. What advice would you give to those who want to live from their art without losing themselves in the process?

Actually, I’m not very good at giving advice, because I believe that what works for one person might not work for another. You’d have to know the person, and give advice considering their actions, their way of communicating, and the possible consequences.

Now that you’re entering what you call “the second half of the game of your life,” what dreams or challenges still excite you?

Well, now they’re no longer dreams — they’re more like necessities. They’re really about continuing to move forward and living within the same art that I’ve always lived with.

If you had to define Rafael Amargo today in one sentence — not the dancer, not the public figure, but the man — what would it be?

Rafael Amargo — the same one — because I’m worth more for what I keep silent than for what others say about me.